Please share research on the real-time hazard detection system………….

Flash flood Detection:

Flash floods are among the most devastating natural hazards globally, causing significant loss of life, property damage, and disruption to communities due to their rapid and unpredictable nature . Effective flash flood hazard detection systems are crucial for mitigating these impacts by providing timely warnings and facilitating rapid response actions . These systems integrate various technologies and methodologies, including hydrological models, meteorological data, remote sensing, Geographic Information Systems (GIS), and increasingly, advanced machine learning and artificial intelligence techniques

The fundamental principle behind flood forecasting models involves the conservation of mass, partitioning precipitation into quickflow and baseflow based on infiltration-excess or saturation-excess mechanisms . Flood hazard can be quantified as a product of the physical process (hazard), the assets or people in its path (exposure), and their susceptibility to harm (vulnerability) .

Components and Methodologies of Flash Flood Detection Systems

- Rainfall Monitoring and Prediction: Local rainstorms are the most significant factor inducing flash floods, especially in mountainous areas 16. Therefore, accurate and timely rainfall data are paramount.

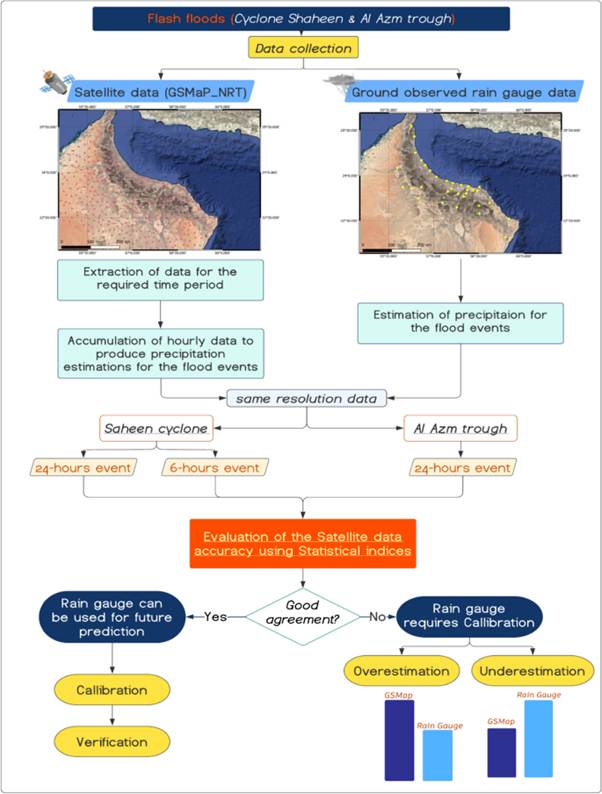

- Radar Imagery and Satellite Estimates: New-generation radars, combined with ground-truthing rain gauges, offer high-resolution and timely rainfall data for flash flood forecasting . Satellite data, such as GPM-based near-real-time precipitation estimates, are crucial for areas with data scarcity, particularly in arid regions prone to flash floods . The accuracy of satellite data can be evaluated using statistical indices and compared with ground-observed rain gauge data, leading to calibration for future predictions .

Flash floods (Cyclone Shaheen)

Source: This flowchart illustrates the process of analyzing flash floods associated with Cyclone Shaheen and the Al Azm trough, focusing on data collection, analysis, and evaluation of satellite and ground-observed data .

- Rainfall Thresholds: Early warning systems often rely on rainfall thresholds, which can be determined using empirical methods (based on historical data), hydrological methods (considering watershed characteristics), and machine learning approaches 19. Empirical methods identify patterns between rainfall and floods but may struggle with spatial and temporal variations, while hydrological methods, though more accurate, require detailed data .

- Rainfall Pattern Identification: A dynamic warning model for flash floods can be improved by identifying rainfall patterns, addressing the randomness and uncertainty of rainfall events .

- Hydrological Modeling: Hydrological models simulate the movement of water across a landscape and are essential for predicting flash floods. These models can range from conceptual, often lumped and parsimonious, to process-based, distributed, and physics-rich .

- Runoff Generation and Routing: Models aim to correctly partition precipitation into quickflow and baseflow and route the resulting water to the outlet . Infiltration models, from empirical formulas like Horton’s to complex Richards equations, are critical for representing the vertical flux of water into the soil .

- GIS-based Hydrological Models: Geographic Information Systems (GIS) technology is extensively used in flash flood risk management for monitoring, analysis, and prediction 10. GIS-based morphometric analysis, utilizing geological, geomorphological, and hydrogeological characteristics, helps in mapping flood hazard degrees and susceptibility in arid regions . Software like the Watershed Modeling System (WMS) is also employed for flash flood simulation .

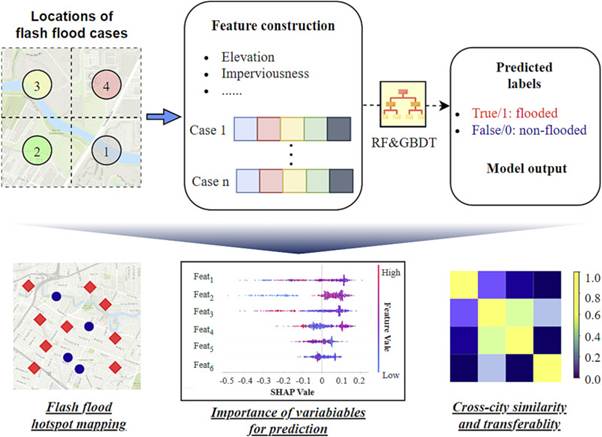

- Urban Flood Prediction: In urban areas, models like the Storm Water Management Model (SWMM) are used to estimate road user delay and assess flood risks based on rainfall scenarios, considering both occurrence probability and economic consequences . Interpretable machine learning models, which incorporate intertwined land and built-environment features, can identify urban flash flood hotspots more efficiently than computationally expensive rainfall-runoff or hydrologic models .

Flash-flood analysis and prediction

Source: 15 This figure depicts a comprehensive workflow for flash flood analysis and prediction, involving flash flood case locations, feature construction (e.g., Elevation, Imperviousness), machine learning models (RF&GBDT), prediction of flooded/non-flooded labels, hotspot mapping, and analysis of variable importance using SHAP values, and cross-city similarity for model transferability .

- Sensor Networks and Real-time Data Collection: Real-time data from sensor networks is crucial for effective flash flood detection and early warning.

- Low-Cost Sensor Systems: Prototypes using Raspberry Pi cameras can detect rising water levels and identify flash floods in real-time, even under varying environmental conditions 5. Low-cost systems utilizing Arduino boards and echolocation for water level measurement, with data transmission via mobile networks, have also been developed .

- Ultrasonic and Infrared Sensors: Urban flash flood detection systems can employ ultrasonic and infrared sensors to provide critical information on flood type, location, and severity, which is vital given the short timescales of urban flash floods .

- IoT Integration: The integration of IoT sensors with machine learning algorithms facilitates early flash flood detection by continuously analyzing crucial environmental variables 9. This technology aims to improve public safety by issuing early and accurate warnings .

- Infrasound Detection: Infrasound signals from water discharges at hydroelectric dams have shown a 79% detection rate for significant water level increases downstream over a 14-year period (2008–2021) 26. This method can provide timely warnings for unexpected discharge events .

- Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning: AI and ML techniques are increasingly being applied to overcome challenges associated with complex hydrological processes and the need for real-time data interpretation in flash flood prediction .

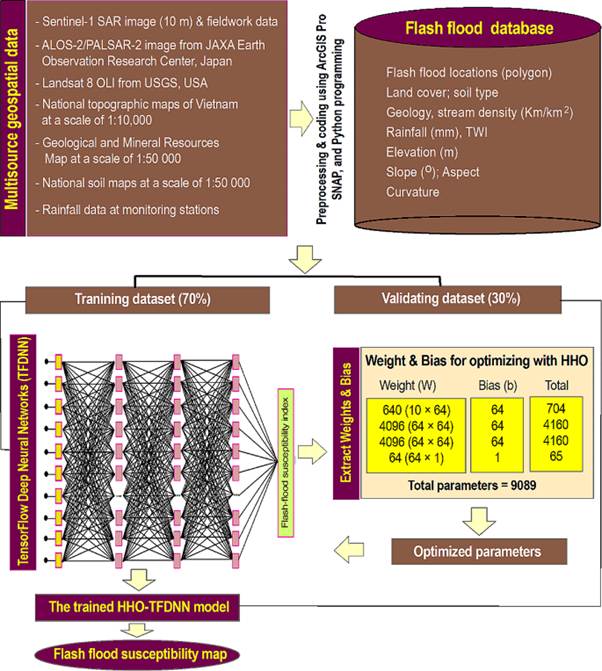

- Deep Learning Models: Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), including Deep 1D-CNN, are used for spatially predicting flash floods by integrating various geospatial data such as geology, soil type, land use, elevation, slope, and rainfall . These models can learn complex relationships between environmental factors and flash flood susceptibility.

Flash-flood susceptibility map

This workflow illustrates the creation of a flash-flood susceptibility map using multi-source geospatial data, deep neural networks (TFDNN), and Harris Hawks Optimization (HHO) for weight and bias optimization .

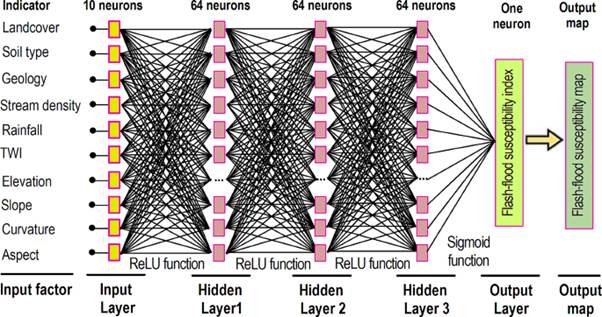

Neural network architecture fo…

This image depicts a neural network architecture with an input layer of 10 neurons representing environmental factors (e.g., landcover, soil type, rainfall, TWI, elevation, slope, curvature, aspect), three hidden layers with neurons each using ReLU activation, and a single-neuron output layer with a Sigmoid function to generate a flash-flood susceptibility index .

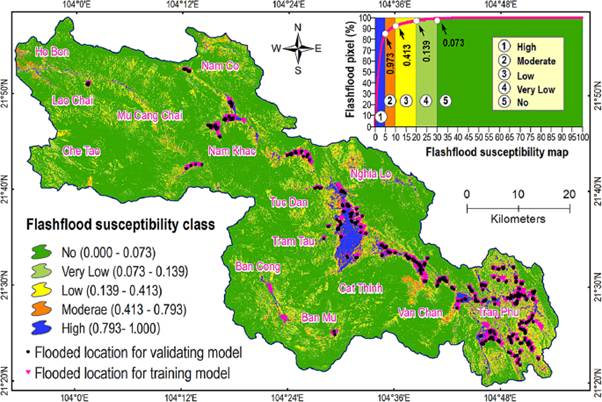

Flash-flood Susceptibility Map

This flash-flood susceptibility map uses color coding to indicate different levels of susceptibility from “No” to “High”, with pink dots marking flooded locations used for training and black dots for validating the model . An attention mechanism, specifically the convolutional block attention module (CBAM), can enhance CNN models for flash flood susceptibility mapping, addressing issues like gradient explosion and overfitting .

- : The YOLOv8 model, a deep learning-based object detection method, can be used for real-time flash flood detection from visual data, demonstrating high confidence scores (e.g., 0.86 and 0.85) in identifying flash flood events in video feeds 29.

Flash flood detection using YO…

This figure shows the YOLOv8 model detecting “flash_flood” with high confidence scores in two different video feeds, indicating its application in real-time monitoring .

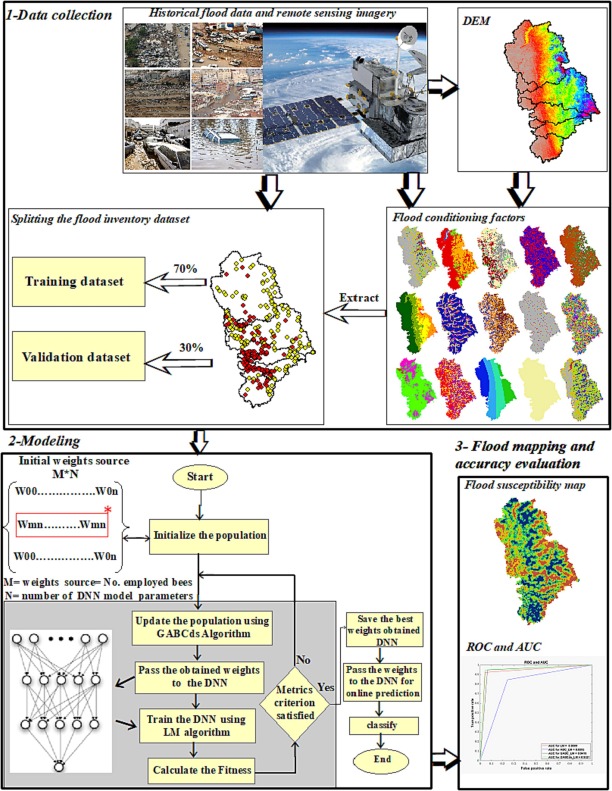

- Hybrid Machine Learning Models: Novel hybrid ML models, like those combining Artificial Bee Colony (ABC) algorithms with Deep Neural Networks (DNN) and Levenberg-Marquardt (LM) algorithms, are being developed for flood subsidence susceptibility mapping 14. These models utilize historical flood data, remote sensing imagery, and various flood conditioning factors to produce flood susceptibility maps with accuracy evaluations .

Flood Susceptibility Mapping

This flowchart outlines the process of flood susceptibility mapping and analysis, covering data collection, modeling using a hybrid ABC-DNN-LM approach, and flood mapping with accuracy evaluation using ROC and AUC curves .

- Remote Sensing and Geographic Information Systems (GIS): Remote sensing provides extensive data over large areas, essential for hazard detection and mapping. SAR (Synthetic Aperture Radar) is a valuable tool for flood inundation mapping due to its ability to penetrate clouds and darkness .

- SAR Time Series Analysis: SAR systems detect floods by observing low radar backscatter from smooth water surfaces, which appear dark. In contrast, rougher land surfaces appear brighter . Time series analysis enables robust flood detection by identifying anomalous changes in backscatter relative to a stable baseline of normal conditions . This method can differentiate temporary floods from permanent water bodies .

- NDWI and MNDWI: Normalized Difference Water Index (NDWI) and Modified Normalized Difference Water Index (MNDWI) distinguish water bodies based on their reflectance properties . MNDWI often outperforms NDWI, especially in urban areas, by better suppressing signals from built-up land, thus reducing false positives . These indices are foundational for rapid flood mapping .

- Integration with DEMs: Fusing SAR data with Digital Elevation Models (DEMs) and hydraulic principles helps in creating physically realistic flood maps and estimating water levels . A pixel is considered inundated only if its elevation is below the estimated water surface elevation and it is continuously connected to a known water source .

- Sentinel-2 Data: The Robust Satellite Technique (RST-FLOOD) has been extended to Sentinel-2 data for mapping flooded areas, providing timely and accurate information on location and extent of affected areas, which is crucial for recovery efforts .

Challenges and Future Directions Despite advancements, challenges remain in flash flood detection. These include the short lead times associated with flash floods, which make accurate forecasting difficult, and the need for more holistic analyses of model uncertainties . Non-identifiability of spatially distributed environmental models further complicates the process .

Future research aims to enhance the integration of multidisciplinary approaches, including artificial intelligence, IoT, and cloud computing, for more robust flash flood early warning and susceptibility prediction systems . This also includes improving model interpretability to facilitate trust and understanding among stakeholders . Furthermore, an objective framework for bivariate risk analysis of flash floods under the compound effect of rainfall characteristics is being developed, aiming to classify flash flood events based on intensity and process using clustering methods 34. The use of agent-based models to simulate human responses to flash flood warnings and improve evacuation performance is also an important area of study

Designing an end-to-end flash flood detection system requires bridging the gap between meteorological observation (what is happening in the sky) and hydrological impact (what happens on the ground), and then successfully communicating that risk to the “last mile.”

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

References ;

- Driving Force Exploration for Flash Flood Based on Mann–Kendall Test and Geographical Detector: A Case Study of Hainan Island, China

- A global sensitivity analysis approach for identifying critical sources of uncertainty in non-identifiable, spatially distributed environmental models: A holistic analysis applied to SWAT for input datasets and model parameters

- A Flash Flood Categorization System Using Scene-Text Recognition

- 2018 IEEE International Conference on Smart Computing (SMARTCOMP)

- Enhancing community resilience in arid regions: A smart framework for flash flood risk assessment

- An agent-based model to simulate human responses to flash flood warnings for improving evacuation performance

- Water, Vol. 16, Pages 3634: Characteristics and Comparative Assessment of Flash Flood Hazard Evaluation Techniques: Insights from Wadi Haily Basin, Eastern Red Sea Coast, Saudi Arabia

Extreme precipitation detection from satellites

Detecting extreme precipitation from space is one of the most difficult challenges in satellite meteorology. Satellites do not “see” rain the way a ground gauge measures it; instead, they infer rainfall intensity by analyzing how cloud particles interact with electromagnetic waves.

The following analysis details the technologies, specific data products, and known limitations involved in this process.

1. The Physics of Detection: How Satellites “See” Heavy Rain

Satellites use two primary parts of the electromagnetic spectrum to detect precipitation. Understanding the difference is key to interpreting the data.

A. Passive Microwave (The “X-Ray”)

This is the most accurate method for detecting heavy rain. Raindrops and ice particles interact strongly with microwave energy.

- Emission: Liquid rain drops emit microwave energy. Over a “cold” background like the ocean, heavy rain appears as a warm signal.

- Scattering: In extreme storms, large ice particles (hail, graupel) lofted high into the cloud scatter microwave energy away from the satellite. This creates a “depression” in the signal, which correlates strongly with heavy convective rainfall.

- Limitation: Microwave sensors are mostly flown on Low Earth Orbit (LEO) satellites. They provide sharp images but pass over a specific location only once or twice a day.

B. Infrared (The “Cloud Top” Proxy)

Geostationary (GEO) satellites sit approx. 36,000 km above the Earth and stare continuously at the same spot.4

- Mechanism: They measure the temperature of cloud tops. The assumption is that colder cloud tops = higher clouds = stronger convection = heavier rain.

- Limitation: This is an indirect relationship.5 Cirrus clouds can be very cold but produce no rain (false alarm). Conversely, “warm rain” processes in tropical cyclones can produce extreme flooding from relatively low/warm clouds, which IR often misses.

2. The “Gold Standard” Products

To solve the trade-off between LEO accuracy and GEO frequency, modern systems use constellations. They combine accurate microwave “snapshots” from LEO satellites and fill in the time gaps using GEO infrared data.

| Product | Full Name | Strength for Extremes | Weakness |

| IMERG | Integrated Multi-sat Retrievals for GPM | The global standard. Calibrated by the GPM Core Observatory radar. Excellent for global coverage. | Tends to underestimate peak extreme intensities due to averaging (smoothing) algorithms. |

| GSMaP | Global Satellite Mapping of Precipitation | Often performs better in identifying orographic (mountain) heavy rain due to specific orographic correction algorithms. | Can have higher false alarm rates in some regions compared to IMERG. |

| CMORPH | CPC Morphing Technique | Uses microwave data primarily and “morphs” (moves) the precipitation features using wind vectors derived from GEO satellites. | struggles when microwave gaps are too long; purely morphing can miss rapid storm intensification. |

3. Why Satellites Struggle with “Extreme” Events

While satellites are excellent at measuring accumulated rainfall over a month, they frequently struggle with instantaneous extreme events (e.g., flash floods).

- Spatial Averaging: A satellite pixel is often 10 X 10 km. If a violent thunderstorm covers only 2 km but is averaged over 100 km², the extreme intensity is diluted, appearing as moderate rain over a larger area.

- The “Warm Rain” Blindspot: Extreme rainfall often occurs in coastal/tropical areas from “shallow” convection (clouds that don’t reach high altitudes). Because these clouds are warm (invisible to IR) and lack ice (invisible to microwave scattering), satellites often miss them entirely.

- Attenuation: In truly massive storms, the rain can be so thick that it blocks the signal entirely (saturation), making it hard to estimate the true peak rate.

4. Advanced Detection Techniques

To improve detection of extremes, scientists are moving beyond simple brightness temperature thresholds:

- Machine Learning / Deep Learning: New algorithms (like PERSIANN-CNN) use Convolutional Neural Networks to look at the “texture” and shape of clouds in IR imagery, not just their temperature. This helps distinguish between a non-raining cirrus cloud and a raining convective core.

- Lightning integration: Since lightning correlates highly with strong vertical convection, sensors like the Geostationary Lightning Mapper (GLM) are being fused with precipitation algorithms to flag convective cores that are likely producing extreme rain rates.

- Bottom-Up Detection (SM2RAIN): Instead of looking at clouds, this method uses satellite soil moisture sensors to detect how much water has hit the ground.11 It is surprisingly effective at capturing accumulated extremes that top-down cloud sensors miss.

Summary Recommendation

- For Analysis: Use IMERG Final Run (research quality, available months later) for the most accurate historical reconstruction of an extreme event.

- For Real-Time Warning: Use IMERG Early or GSMaP Now, but apply a correction factor, as the raw data will likely underestimate the peak rainfall intensity of a flash-flood event by 30-50%.

Extreme precipitation detection from satellites

For extreme precipitation detection from satellites, the most useful sensors fall into three operational classes (often used together). The key trade-off is accuracy vs refresh rate.

1) Low Earth Orbit (LEO) active radar: best for “how intense and where in the column”

Primary sensor type: Spaceborne precipitation radar

- GPM Dual-frequency Precipitation Radar (DPR) (Ku + Ka): provides 3D precipitation structure and is one of the best spaceborne references for extreme-rain intensity and vertical profiles.

- TRMM Precipitation Radar (PR) (legacy): the first spaceborne rain radar, widely used historically for intense tropical rainfall analyses.

- Strengths for extremes: direct sensitivity to precipitation in the column; helps separate convective/stratiform structures and improves “ground truth” for calibrating other satellite products.

Limits: narrow swath and intermittent overpasses (not continuous monitoring).

2) LEO passive microwave (PMW): best global “rain-rate signal” through clouds (but with gaps in time)

Primary sensor type: Microwave imagers/sounders used in precipitation retrieval (the workhorse for global heavy rain detection)

Examples:

- GPM Microwave Imager (GMI): designed to measure light to heavy precipitation as part of GPM.

- AMSR2: provides data used for global precipitation retrieval among other hydrometeor variables.

- SSM/I–SSMIS family (DMSP): long-running PMW imagers/sounders with precipitation products and broad use in multi-satellite precipitation datasets.

- ATMS (JPSS/Suomi NPP): primarily a temperature/moisture sounder, but also supports precipitation-related applications/products.

Strengths for extremes: PMW is physically closer to precipitation microphysics than IR cloud-top methods; strong basis for detecting/quantifying intense rain.

Limits: revisit gaps (hours), coastal/orographic complexities, and retrieval challenges over land for certain regimes.

3) Geostationary (GEO) IR imagers: best for continuous monitoring and “rapid detection,” weaker for true intensity

Primary sensor type: Visible/IR multi-spectral imagers providing rapid-refresh cloud-top observations

Examples/products:

- GOES-R ABI rainfall-rate/QPE produces instantaneous rainfall rate estimates used in flood forecasting workflows.

- Himawari-8/9 AHI (ABI-class): high temporal sampling for fast storm evolution monitoring.

- Meteosat SEVIRI: widely used in convective/heavy-rain detection research and IR-based rainfall estimation approaches.

- Strengths for extremes: continuous “watching” (minutes-scale), very good for detecting rapidly growing convective systems and tracking them.

Limits: IR sees cloud tops, not rain directly; warm-rain and some extreme events can be misestimated.

4) Lightning mappers: powerful proxy for convective intensification (not rain rate)

- GOES Geostationary Lightning Mapper (GLM) measures total lightning and helps identify intensifying thunderstorms (often correlated with severe convection).

- 5) The operational answer in practice: use blended multi-satellite precipitation products

If your goal is operational extreme-rain monitoring (rather than instrument-level science), you typically use a fusion product such as:

- IMERG (Integrated Multi-satellitE Retrievals for GPM): combines GPM constellation information (PMW + GEO IR, with calibration/intercalibration steps) to produce gridded precipitation estimates and near-real-time runs. What to choose (rule of thumb)

- Need best intensity/structure: GPM DPR (+ PMW)

- Need global heavy rain detection (physics-based) with acceptable latency: LEO PMW constellation / IMERG

- Need minute-by-minute situational awareness: GEO IR (ABI/AHI/SEVIRI) + optional lightning proxy

Where ML/AI fits (if you are building an extreme-rain detector)

A common modern pattern is GEO IR (+ lightning) → calibrated against PMW/radar, using deep learning to improve detection skill and reduce false alarms; this is an active line of operational development for GOES-style precipitation retrieval enhancement.

Flash flood detection system (end-to-end design)

A flash flood detection system is operationally effective when it combines: (1) high-frequency rainfall estimation/nowcasting, (2) fast hydrologic response modeling at small-basin scale, and (3) clear, standardized warning products and dissemination. Globally, the World Meteorological Organization’s Flash Flood Guidance System (FFGS) is an established reference implementation for building national/regional capacity for flash flood warnings.

1) Core system architecture

A. Observations and rainfall estimation layer

Use the best available mix (in priority order):

- Weather radar QPE (if available): highest spatiotemporal resolution for convective extremes.

- Gauge networks: ground truth for bias correction and threshold verification.

- Satellite precipitation for gap-filling and national coverage (especially where radar/gauges are sparse). NASA’s IMERG provides near-real-time precipitation estimates and is commonly used in hydromet hazard monitoring; its “Early” run is near-real-time with around ~4 hours latency, and “Late” around ~14 hours per NASA’s technical documentation.

Output: gridded rain rate and accumulations at multiple durations (e.g., 15/30/60/180 minutes).

B. Basin-scale hydrologic detection/forecasting layer

Two widely used operational concepts:

- Flash Flood Guidance (FFG): “How much rain over a duration is needed to cause flooding,” conditioned on current soil moisture/streamflow conditions. (This is a key idea behind many operational workflows.)

- Distributed hydrologic modeling + thresholds: run a fast rainfall–runoff model and trigger on indicators such as unit streamflow (runoff per unit basin area), rapid rise rate, and basin wetness.

A concrete example is NOAA/NSSL’s FLASH system, built to improve flash flood warning specificity; it uses the CREST hydrologic model and produces high-resolution, rapidly updated hydrologic fields (soil moisture/streamflow) to support warnings.

Output: basin/stream-segment “threat” scores, exceedance probabilities, and short-fuse forecasts.

C. Impact and prioritization layer (what matters, where)

Flash flood detection becomes much more actionable when converted to impact-based outputs:

- population/infrastructure exposure in threatened basins

- critical roads/bridges likely to be overtopped

- urban hotspots (poor drainage) vs rural headwaters

Output: ranked alert list + map of potential impacts.

D. Warning generation and dissemination layer

Adopt a standards-based alert object so the same warning can be broadcast across multiple channels (SMS, cell broadcast, apps, radio/TV crawlers, sirens, CAP feeds). The Common Alerting Protocol (CAP) is the widely used all-hazards standard for this purpose.

Output: CAP alerts with polygon/area, severity/urgency/certainty, guidance text, and validity time.

2) Detection logic (recommended “trigger stack”)

A robust flash flood detector should not rely on a single signal. A practical trigger stack is:

- Rainfall trigger (observation/nowcast):

- Intensity and accumulation exceed thresholds at multiple durations (e.g., 30–60 min for urban; 1–3 h for small basins)

- Antecedent wetness trigger:

- soil moisture index / API / modeled saturation (lowers rainfall threshold)

- Hydrologic response trigger:

- modeled unit streamflow exceeds bankfull proxy

- rapid rise rate flags “imminent” conditions

- Confirmation trigger (where available):

- gauge stage rise, crowdsourced reports, camera/IoT signals

This mirrors how operational “guidance” systems (FFG/FFGS-style) are intended to translate rainfall into small-basin flood threat.

3) Where AI/ML improves performance (without replacing physics)

AI typically adds the most value in three modules:

A) Rainfall nowcasting (0–3 hours)

Spatiotemporal ML models improve short-lead detection of convective bursts that drive flash floods, especially when fused with radar + satellite.

B) Bias correction / data fusion

ML post-processing to:

- correct satellite/radar biases against gauges

- fuse multi-source precipitation into a single best-estimate QPE/QPN

C) Learned impact models

Supervised models that map “hazard + basin state + exposure” to likely impacts (road flooding probability, affected population), trained on historical events.

For operational credibility, keep ML “bounded” (monitor drift, enforce physical constraints where possible, and require human-in-the-loop sign-off for high-severity warnings).

4) Minimum viable vs advanced implementation

Minimum viable (works almost anywhere):

- satellite QPE (e.g., IMERG NRT) + gauges (if any)

- basin delineation from DEM + simple runoff index / threshold model

- CAP-based alerting + SOP playbooks

Advanced (higher skill, lower false alarms):

- radar QPE + spatiotemporal nowcasting

- distributed hydrologic model (FLASH/FFG-style workflow) with calibration

- rapid inundation approximation for key urban corridors

- automated verification dashboards and continuous learning loops

5) Operational essentials (often neglected)

Interagency workflow: forecaster ↔ disaster management ↔ local responders (FFGS emphasizes operational capacity-building and coordination).

Threshold governance: who sets/approves thresholds per basin and how updates happen after events

Verification: event-based scoring (POD/FAR/CSI by threshold and lead time) and post-event reviews

Redundant communications: CAP + non-digital fallbacks for high-risk communities

Model: 2

Designing an end-to-end flash flood detection system requires bridging the gap between meteorological observation (what is happening in the sky) and hydrological impact (what happens on the ground), and then successfully communicating that risk to the “last mile.”

Below is a technical architectural design for such a system, focusing on latency reduction and high-precision monitoring.

Phase 1: Multi-Sensor Data Ingestion (The “Eyes”)

Flash floods occur too quickly for any single sensor to capture perfectly. The system must ingest a “constellation” of data sources into a central Data Hub.

Data Source | Specific Technology/Product | Role in Flash Flood Detection |

Satellite (Precipitation) | GPM (IMERG Early) or GSMaP_NRT | Provides the broad spatial view. Correction: Must be bias-corrected in real-time using ground gauges. |

Satellite (Lightning) | GOES-GLM or MTG-LI | Critical Proxy: Lightning frequency correlates strongly with vertical updraft velocity. A sudden “lightning jump” is often the earliest precursor to the extreme rainfall rates that cause flash floods. |

Ground Radar | X-Band or C-Band | If available, offers the highest resolution for calculating quantitative precipitation estimation (QPE). |

IoT Sensors | Ultrasonic Level Sensors & Soil Moisture | “Ground truthing.” Soil moisture data (saturation level) determines if the ground will absorb the rain or immediately produce runoff. |

Phase 2: The Processing Core (The “Brain”)

This is where the raw data is converted into actionable intelligence. This requires a High-Performance Computing (HPC) environment or a scalable Cloud Cluster.

- The Hydrometeorological Chain

- Nowcasting (0–6 Hours): Use Optical Flow or AI algorithms (e.g., ConvLSTM) to extrapolate current radar/satellite images 1–2 hours into the future. This is the first line of defense.

- NWP Modeling: Run a rapid-update cycle of WRF (Weather Research and Forecasting).

- Configuration: High resolution (1-3 km) with explicit convection (no cumulus parameterization).

- Assimilation: Assimilate radar reflectivity and lightning data to “warm start” the model.

- Hydrological Routing: Feed the rainfall output (QPE/QPF) into a hydrological model like WRF-Hydro or HEC-HMS.

- Output: This calculates Streamflow (m/s) and Surface Runoff. It answers: Will the river banks overflow?

- Impact-Based Forecasting (IBF)

Instead of warning “50mm of rain expected,” the system calculates impact.

- Overlay: Flood depth maps vs. Exposure Data (Population density, Critical Infrastructure, Agriculture).

- Trigger: If water level > threshold} AND population > 0, generate Red Alert.

Phase 3: Alert Generation & Dissemination (The “Voice”)

Speed is critical. The system must bypass congestion.

- The Common Alerting Protocol (CAP)

The “Brain” outputs a CAP-formatted message (XML). This standard ensures all downstream systems (Sirens, TV, Mobile) understand the severity, location (polygon), and instruction.

- Telecommunication Channels

- Cell Broadcast (LBAS):

- Mechanism: The Mobile Network Operator (MNO) broadcasts the message to every phone connected to cell towers within the danger polygon.

- Advantage: Zero latency, no network congestion (uses signaling channels), works on non-smartphones. This is the gold standard for immediate life safety.

- SMS Aggregators / SMPP:

- Mechanism: Sends bulk SMS to registered databases (e.g., First Responders, Village Chiefs).

- Advantage: Targeted. Can ask for confirmation.

- Disadvantage: Slower; subject to queueing delays during storms.

- USSD (Unstructured Supplementary Service Data):

- Mechanism: Users dial a code (e.g., *123#) to “pull” the latest status.

- Advantage: Works on 2G; excellent for farmers or local leaders to check river levels proactively.

System Architecture Diagram

To visualize how these components connect, here is the architectural flow:

Summary of Logic Flow

- Detect: Satellite sees a “Lightning Jump” + Radar sees high reflectivity.

- Predict: AI Model predicts 100mm rain in the next hour over District X.

- Model: Hydrological model calculates that District X’s soil is saturated; Runoff will trigger a flash flood.

- Target: GIS system identifies 5 villages in the path.

- Warn:

- Civil Defense: Receives CAP alert on dashboard.

- Public: Phones in the 5 villages scream with a Cell Broadcast alert.

- Local Leaders: Receive SMS instructing to open shelters.

Still to feed huge information……….Exploring the most robust ICT system for surface, atmospheric, and sea surface observation, real-time data acquisition, on-the-fly processing in, and displaying in MHEWS for awareness.